A Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: The Enduring Legacy of Fahrenheit 451

- Between Spines

- Feb 23, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 5, 2021

“The things you're looking for, Montag, are in the world, but the only way the average chap will ever see ninety-nine percent of them is in a book."

Ray Bradbury’s seminal 1953 work Fahrenheit 451 is one of our world’s most famous novels. Written during a time of Cold War paranoia, Bradbury offered a vision for the future in which fires were no longer put out but started. One man among many tasked with this job is our protagonist, Guy Montag. A central theme of the book is the exploration of society’s reliance on government commissioned ‘news’ and how people react with such reception to propaganda by wiring into screens and radio programmes.

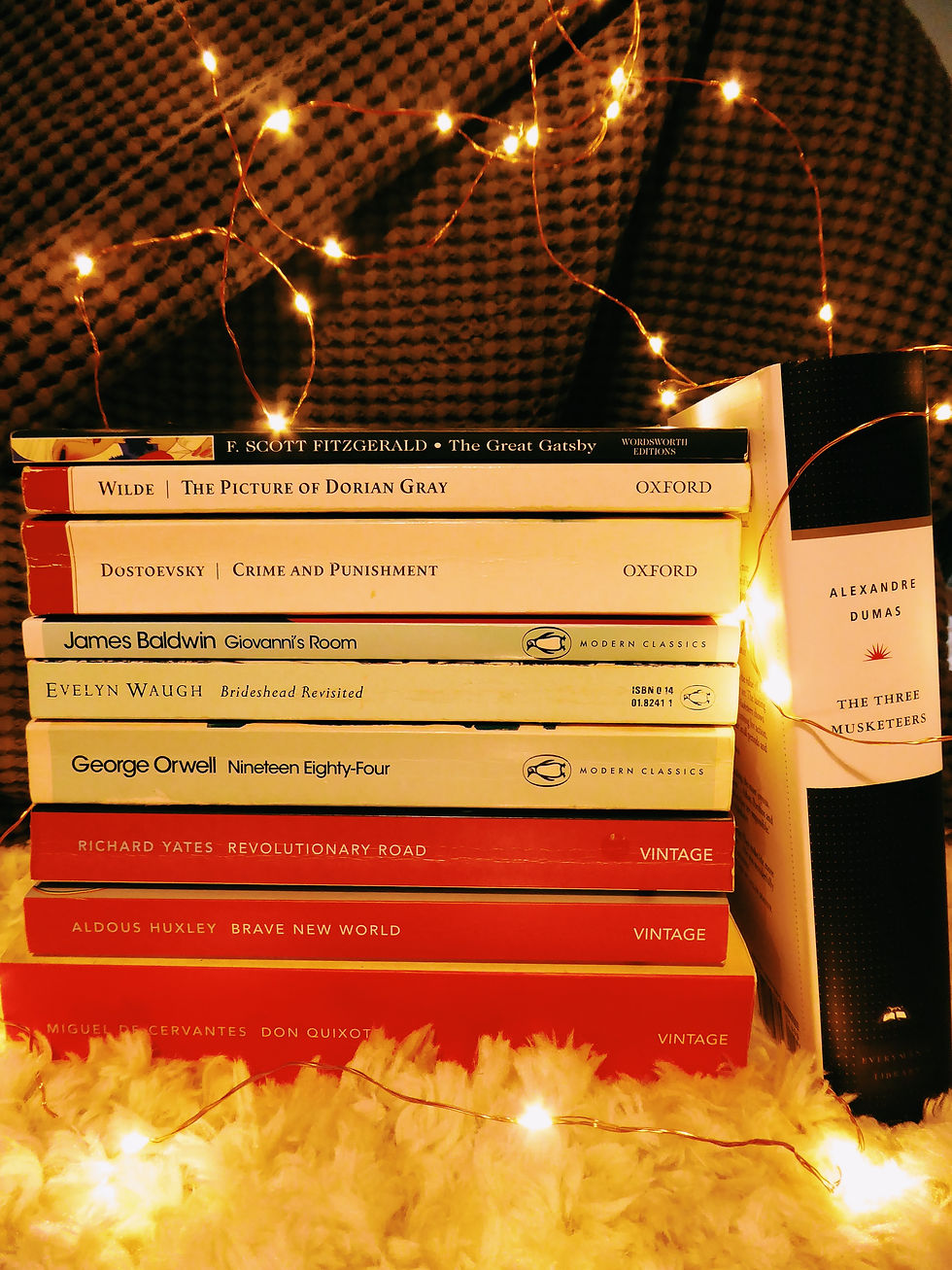

Many have called Bradbury’s novel prophetic and it has been compared to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eight Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. To go further and understand Fahrenheit more deeply, we should address the historical context around the book’s publication, how the novel has been received, and what Bradbury himself perceived of its legacy during the 21st century.

Fahrenheit’s protagonist Montag lives in a nondescript suburb with his wife Mildred, who tacitly undertakes a monotonous existence of consumption. She soaks up government programmes and refers to fictional characters on her screens as ‘family’. Guy and Mildred’s living room has screens across three walls, and Mildred is insistent upon Guy using his salary to finance a new screen installation on their fourth wall, completing her fantasy. The impacts of such consumption upon the mind are central to the appeal of Fahrenheit and key to Bradbury’s motivations as a writer.

As Guy begins to question his place in society, he alienates Mildred and her friends. They are alarmingly resistant to Montag’s beliefs on war and freedom and their differences manifest in conversations that are devoid of emotion or compassion. When Guy asks one of Mildred’s friends about her husband and his whereabouts, she replies: “He’ll be back next week… a quick war… I’m not worried”, continuing to talk nonchalantly about how “it’s always someone else’s husband who dies.” Conflict is discussed with indifference, which exemplifies Bradbury’s perception of real societal attitudes towards the Cold War in America during the 1950s.

Bradbury clearly exaggerated how the middle classes spoke about war in his depiction of Mildred and her friends in Fahrenheit. However, as Sam Weller notes, it is not difficult to understand what inspired this cynical vision. As Weller argues, ‘it appeared as if economically prosperous Americans had forgotten the war years during the 1950s'.

Bradbury supremely captured this idea through the portrayal of Granger. One of the novel's 'literary exiles’, Granger once escaped the city to join a group of people who recollect passages from books so that they do not forget them. Granger wisely explains, “We're remembering. That's where we'll win out in the long run.” Bradbury’s tone here is cautionary, placing the onus upon the people who acquiesced to the shifting dynamic of society, from one which championed freedom of thought to one which now celebrates progress through forgetting.

Elucidating on this distinction between those who clung to their individual agency and those who surrendered themselves to a routine of hearing more ‘factoids’, we see that Bradbury’s novel spoke to a generation who were witnessing a seismic change to their world after World War Two. As David Fox argues, ‘Mildred and Guy’s hedonistic society would have resonated with readers and made them realise that America in the 1950s was not too far off from the unsettling society in Fahrenheit.’

Clearly, Bradbury extrapolated the potential dangers of mass information consumption with immense hyperbole. However, if we recognise how profound the author’s vision was considered in the 1950s, then surely Bradbury’s prophecy is distinctly more terrifyingly and accurate today as we live in a world of immensely sophisticated connectivity, characterised by a plethora of various social and recreational media channels to wire ourselves into 24/7.

Another key feature of the world which Bradbury constructed is the vast metropolitan landscape of Montag’s community. This is another example of how Bradbury witnessed a trend being set in 1950s America, overstated for dramatic effect in the novel but no less poignant to consider. Montag’s suburban existence is devoid of any environment other than one within the city limits, contributing greatly to families’ self-absorption and insularity.

Why would different households want to mix with each other, conducting inane conversations when they could be entertained during every waking hour within their own homes? Fox links this back to 1950s America, maintaining, ‘families that bought into the idea of mass culture within their suburban lives meant that the family became more fragmented, with a decline in agriculture and small-town communities.’ The almost exclusive city/suburban setting of the novel encapsulates this idea.

Why did conformity become synonymous with the 1950s? As Weller has noted, there was a marked increase in economic prosperity after the war. Therefore, as the times got better for the middle classes, why would they resist new changes that were 'for the better’? Fox expands on this, suggesting that ‘mass culture and homogenisation in the 1950s led to unprecedented pressure to conform.’

What did Bradbury make of these ideas when viewed in a modern context? In 2007, Amy E. Boyle Johnston wrote in LA Weekly about her interview with Bradbury, who passionately argued that the book ‘was about the moronic influence of popular culture through local TV news and the proliferation of giant screens and the bombardment of factoids, the competition programmes.’

Bradbury portrayed a society of people who listened to anything but questioned nothing. He told Johnston, ‘They tell you when Napoleon was born but not who he was…They stuff you with so much useless information, you feel full.’ After all, as Montag’s Captain, Beatty, tells him, “You ask why to a lot of things and you wind up very unhappy indeed.”

What were tangible indications of such trends in the real world? Bradbury wrote to a friend, “This sort of hopscotching existence makes it almost impossible for people, myself included, to sit down and get into a novel again. We have become a short story reading people, or, worse than that, a QUICK reading people.” Who does Bradbury hold most responsible for this? The people, addicted to entertainment.

This is backed up by statistical evidence. As Fox notes, in the fiscal year 2009, 41% of states reported declining state funding for US public libraries, with some budgets slashed by 30%. Talking to Johnston in 2007, Bradbury said he was 'far more concerned with the dulling effects of TV on people than he was on the silencing effect of a heavy-handed government.’ Therefore, we see the cause and effect of how governments oversaw the mass increase of televisions during the Cold War in America, then were forced into slashing library budgets as more people stayed at home to be entertained instead of checking out books for their pleasure.

However, Bradbury still took some solace in the success of Fahrenheit and it's legacy in the 21st century. He astutely observed that his works ‘ became the sort of classics that kids read for fun and adults re-read for their wisdom and artistry.’ Central to Bradbury’s success with Fahrenheit was how he managed to appeal to the ‘adolescent minds’ of science-fiction readers as well as speaking to a mature, more middle-class audience.

To encapsulate the sincerity of Bradbury’s classic, Fox sums it up superbly, writing, ‘Ray Bradbury helped to expose America to itself, for better or worse, when many other authors were afraid to do so.’ This argument perfectly embodies the enduring nature of Fahrenheit.

The perfect irony here is that this article falls into the category of ‘short reads’ which Bradbury termed shortly before his death in 2012. Furthermore, this article has come into being purely because of the internet’s easy-to-navigate interface. Thus we see the inescapable element of the internet. It is cheap and easy, much like everything else we consume today.

In relation to our mission to write passionately about our favourite literature and bring our readers closer to our most cherished books, the forums have diminished and the platforms are more limited. To write about literature, where else can you write about your passions and how do you get more people to read your content?

It is clear that the easiest, most accessible, and most effective way of doing so is on the internet, a transcendental concept which nobody foresaw during the Fahrenheit era. Nonetheless, Bradbury was clearly onto something when he depicted a society ‘being turned into morons.’ Food for thought.

To keep up to date with all of my reviews, follow me on Goodreads.

Comments